January 16, 2026

Sharon McGuinness, PhD

Executive Director

European Chemicals Agency

Telakkakatu 6, P.O. Box 400

FI-00121

Helsinki, Finland

via website: https://echa.europa.eu/harmonised-classification-and-labelling-consultation/-/substance-rev/80601/term

The International Association for Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial Research (IADR), which represents over 10,500 researchers around the world whose mission is to drive dental, oral, and craniofacial research for health and well-being worldwide, appreciates the opportunity to share our evidence-based perspectives on the proposed harmonized classification and labelling (CLH) of sodium fluoride. IADR supports rigorous, evidence-based chemicals regulation and transparent, methodologically sound, hazard classification, and applauds the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) for considering the safety of sodium fluoride to be protective of public health and the environment. To respond to this request for comments, IADR engaged its Science Information Committee, toxicological experts within its membership, and its Board of Directors.

IADR is deeply concerned that the CLH’s key conclusions - particularly on the detrimental effects of sodium fluoride on developmental neurotoxicity/cognition, reproductive toxicity, and thyroid-mediated endocrine disruption - significantly overstate this conclusion given substantial methodological limitations, such as exposure assessment, confounding controls, heterogeneity, and mechanistic coherence across the cited toxicological and epidemiological literature. The evidence presented in the ANSES dossier does not support a change to the current Annex VI classification and labelling entry for sodium fluoride.

The optimal level of fluoride has long been recognized by global health authorities, including the World Health Organization (WHO), as the most effective and scientifically validated ingredient for preventing dental caries. Optimal levels of fluoride are added to public water supplies in some European countries while others add fluoride to salt or milk. Fluoride toothpaste and mouthwashes containing sodium fluoride are included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, underscoring its proven cost-effectiveness, safety, and role in reducing health inequalities. The WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan 2023–2030 identifies oral diseases as among the most prevalent noncommunicable diseases worldwide, and highlights the use of fluoride (in toothpaste, mouth rinses, and community water fluoridation) as a cornerstone strategy for global oral health promotion. The WHO further calls on all Member States to ensure universal access to affordable fluoridated oral care as part of essential primary oral healthcare.

The WHO has concluded that “the weight of evidence does not support fluoride as a cause of cancer in humans” and that “pregnancy-outcome studies indicate no apparent relationship the rates of Down syndrome or congenital malformations and the consumption of fluoridated drinking water” (WHO 2004 and 2022). In concurrence, the individual Member States across the globe have concluded that expert panels “have not found convincing scientific evidence linking community water fluoridation with systemic disorders such as increased cancer risk or low intelligence” (US CDC, 2024).

Given the proven importance of fluoride in water systems, fluoridated salt or milk schemes, fluoridated toothpaste and mouthwash, to prevent dental caries, any reclassification of sodium fluoride as a reproductive toxin and/or endocrine disrupter will have serious consequences for the oral and systemic health of global populations. Because the CLH is hazard-based, it is essential that the evidence base clearly demonstrates adversity at doses relevant to foreseeable human exposures for the uses in scope; otherwise, hazard conclusions risk being erroneous, as they would be driven by high-dose artifacts and confounding. Therefore, IADR urges a very critical review of any and all evidence of potential negative consequences of sodium fluoride before adopting any new classifications.

Developmental neurotoxicity and cognition: concerns with “sufficient evidence” conclusions (CLH Report Section 11.1.2.2, pages 133-159)

Recent research in neuroscience and developmental psychology shows that brain development and cognitive abilities remain plastic well beyond early childhood, undermining the idea that IQ is fixed after the first few years of life (Larsen et al, 2018). In fact, adolescence is a neurobiologically critical period for the development of higher-order cognition (Mousely et al. 2025). In this context, the recent longitudinal study by Warren et al. (2025) of U.S. adolescents and adults is highly significant because it assessed long-term effects. This study showed that children exposed to recommended levels of fluoride in drinking water exhibit modestly better cognition in secondary school, an advantage that is smaller and no longer statistically significant at age ~60 (Warren et al, 2025). This compelling study warrants further research including more specific assessment of exposure.

The CLH report tabulates human studies of children and cognition, as well as studies on experimental animal models, and states that it provides sufficient evidence associating increased fluoride exposure during pregnancy with decreased IQ and impaired cognitive function in children. The comments below highlight several important scientific issues that necessitate a more cautious interpretation of these studies:

- Proxy exposure measurement and misclassification (Section 11.1.2.2.1 – Table 23, p. 135 - 139)

True fetal/child target-tissue exposure in the brain is unknowable; therefore, most exposure measures rely on proxies such as spot urinary fluoride that can vary substantially day-to-day and introduce exposure misclassification. The CLH report ignores studies that use other individual exposure measures. The study by Do et al. (2025) assessed residential history to postcode-level fluoride concentrations in the public water database and dental fluorosis exposure measures having a distinct advantage over the spot urinary fluoride measure. In that study, the authors reported no evidence that early childhood fluoride exposure adversely affected cognitive neurodevelopment. Therefore, this study should be included within the report analyses.- Do LG, Sawyer A, Spencer AJ, Leary S, Kuring JK, Jones AL, Le T, Reece CE, Ha DH. (2025). Early Childhood Exposures to Fluorides and Cognitive Neurodevelopment: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. J Dent Res. 104(3):243-250.

- Epidemiological limitations (Section 11.1.2.2.1 – Table 23, p. 135 - 136)

It is critical that ecological study designs, confounding adjustments (including co-exposures, nutrition, iodine status), small sample sizes, and context-specific exposures be more explicitly weighted in the human-relevance narrative. For example, the studies in Mexico raise concerns about the concurrent exposures to lead that were identified, although putatively controlled for. Additionally, clustering in human epidemiological studies (e.g., children nested within villages, schools, or communities) creates the same statistical problem as litter effects in animal studies, because individuals within a cluster are correlated, not independent. When clustering is ignored, the result is misleading precision, inflated sample size, and potentially spurious associations. The MIREC (6 cities) and ELEMENT (3 sub-cohorts recruited from hospitals) studies did not adequately address clustered observations. - Motor and Sensory Confounding in Cognitive Outcomes (Section 11.1.2.2.1 – Table 24, and pgs.158-159)

The report includes a description of fluoride exposures on locomotor function. However, it is important to note that this may then bias any cognitive tests, as these require motor function. Correlations across these measures could have assisted in grounding any conclusions based on this data. Similar conclusions would be pertinent to any loss of sensory function, but this also does not appear to have been addressed in the report. Furthermore, the report largely minimizes these effects by concluding that changes in the hippocampal and prefrontal cortex in neuroanatomical, functional and cellular modifications were seen. Again, these conclusions are overstated. - Lacking analysis of levels of exposure (Section 11.1.2.2.1 – p.139)

There is no discussion of the levels of exposure at which concerns are evident. Additionally, no concentration-effect curve is presented and no forest plots are shown. Furthermore, in one study in which maternal urinary fluoride was collected and in which fluoridated water concentrations were 0.81 mg/l, there is an opposite effect of what was seen in other studies. There was no discussion as to what this discrepancy might reflect. - Selective Reporting and Publication Bias (Section 11.1.2.2.1 – Table 23)

(i). The report asserts that “the assessment of evidence for neurodevelopmental toxicity allows the inclusion of eight studies of good quality and reliability (Table 23)”. However, it omits the Odense Childhood Cohort study in Denmark, which found no association between maternal urinary fluoride and children’s IQ. (ii). Higher-quality longitudinal and quasi-experimental studies that report null or inconsistent associations in exposure ranges relevant to community prevention contexts were also excluded within the CLH report analyses and should be included:- Aggeborn L, Öhman M. (2021). The effects of fluoride in drinking water. Journal of Political Economy. 129(2):465-491.

- Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Ramrakha S, Moffitt TE, Zeng J, Foster Page LA, Poulton R. (2015). Community Water Fluoridation and Intelligence: Prospective Study in New Zealand. Am J Public Health. 105(1):72-76.

- Dewey D, England-Mason G, Ntanda H, Deane AJ, Jain M, Barnieh N, Giesbrecht GF, Letourneau N; APrON Study Team. (2023). Fluoride exposure during pregnancy from a community water supply is associated with executive function in preschool children: A prospective ecological cohort study. Sci Total Environ. 891:164322.

- Warren JR, Rumore G, Kim S, Grodsky E, Muller C, Manly JJ, Brickman AM. (2025). Childhood fluoride exposure and cognition across the life course. Sci Adv. 11(47):eadz0757.

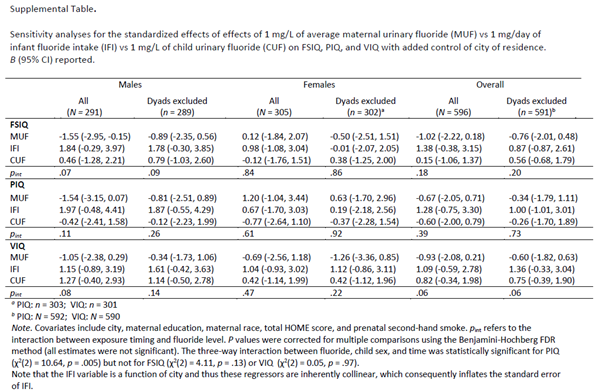

(iii). The MIREC study was sliced into 8 publications. However, it is important to note that the mean IQ score was 108 in fluoridated and 108 in non-fluoridated communities. Therefore, IQ was not a public health concern in this convenience sample. (iv). Although the Farmus et al. (2022) study was referenced to support the conclusion that the association between prenatal fluoride exposure and IQ was significant, the CLH report did not consider the Farmus et al. addendum (below) that contradicted this conclusion (Farmus et al. 2021). It is important to note that none of the 54 coefficients (FSIQ, PIQ, VIQ during pregnancy, infancy, and childhood in boys and girls) is statistically significant. Furthermore, as the authors used a different IQ tester in each of the six cities, controlling for the city is critical. The authors’ justification that the city is correlated with infant fluoride exposure (IFI) does not apply to the maternal urinary fluoride coefficients (Guichon et al. 2024a).

Farmus et al. 2021. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons, and none of the estimates were significant. Even if the IFI coefficient is affected by the collinearity, this analysis should not affect the MUF coefficients.

Therefore, IADR recommends that the Risk Assessment Committee (RAC) explicitly (i) downgrade certainty where inconsistency / heterogeneity is high and unexplained, and (ii) ensure conclusions distinguish more clearly between findings from fluorosis-endemic / high-exposure settings and evidence at low-to-moderate exposures.

Inclusion of high-concentration animal exposure studies (Section 11.1.2.2.2 – Table 24, and p. 158 - 159)

The US National Toxicology Program (NTP) report, the subsequent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) review, and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) report, contradict the CLH report in many important ways. Notably, these major independent evaluations all converge on the conclusion that animal studies of fluoride are not informative for assessing human developmental neurotoxicity at community exposure levels. The NTP animal-focused review found learning and memory effects mainly at very high doses, with most studies suffering from small sample sizes, poor control of systemic toxicity, inadequate handling of litter effects, and non-standard behavioral methods (US NTP, 2019a). NASEM, in reviewing the draft NTP monograph, agreed that animal available evidence is methodologically weak, highly heterogeneous, and largely unsuitable for quantifying neurodevelopmental risk in humans (NASEM, 2021). Guth et al.’s risk assessment reached similar conclusions, emphasizing that the available animal data are high-dose, low-quality, and yield margins of exposure that are reassuring at current fluoride intakes. Together, these reviews show that animal studies cannot credibly be used to claim that fluoride at levels used in community water fluoridation is a proven developmental neurotoxicant.

Additionally, limitations of the animal studies included in this report, aside from only testing a single exposure concentration and including studies without a control group, were not addressed within the CLH report. This includes litter-specific effects because pups from the same litter are not independent units of analysis. When litter is ignored, the statistical analysis becomes invalid, the study’s precision is exaggerated, and the findings, whether positive or null, cannot be trusted. Furthermore, the order of behavioural tests is also not addressed, despite evidence that behavioral effects from one paradigm can feed forward to influence subsequent behavioral tests.

Studies have also shown that the margin of exposure (MoE) between no observed adverse effect levels (NOAELs) in animal studies, and the current adequate intake (AI) of fluoride (50 μg/kg b.w./day) in humans, ranges between 50 and 210 depending on the specific animal experiment used as reference. Even for unusually high fluoride exposure levels, an MoE of at least ten was obtained. Furthermore, concentrations of fluoride in human plasma are much lower than fluoride concentrations in animal studies that cause effects in cell culture experiments.

Overinterpretation of high-dose blood-brain barrier evidence (Section 9, p. 13 - 14)

The CLH report states (p. 13) that “evidence from the literature also show that exposure to fluoride can damage the blood-brain barrier (Qing-Feng et al., 2019).” However, the cited study has limited relevance for human health assessment and hazard classification because Wistar rats were exposed via drinking water to 200 mg/L fluoride for 24 weeks, approximately 286-fold higher than the common regulatory target level for community water fluoridation (0.7 mg/L). Even acknowledging interspecies differences in fluoride toxicokinetics (e.g., absorption and skeletal accumulation), the extreme exposure conditions used in this study substantially limit interpretability and preclude meaningful extrapolation to foreseeable human exposures.

Despite these limitations, the CLH report subsequently concludes (p. 14) that “fluoride can cross the placental barrier, damage the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in various regions of the brain.” In relation to blood-brain barrier effects, this statement is presented as a generalized toxicokinetic property, yet it appears to be underpinned primarily by high-dose animal evidence generated under unrealistic exposure conditions, without corroborating data at exposure levels relevant to human populations. Using such high-dose findings to support broad statements regarding blood-brain barrier damage and developmental relevance, without adequate qualification of dose relevance, risks overinterpretation and may bias subsequent weight-of-evidence conclusions. Accordingly, this evidence should be treated with extreme caution in the context of hazard classification.

Therefore, it is critical that data across diverse exposure contexts not be synthesized. It is important to distinguish studies conducted in high-fluoride endemic settings from those relevant to community prevention exposure ranges, as extrapolation across these contexts introduces substantial uncertainty.

Reproductive Toxicity: Endpoint Relevance, Study Design Limitations, and Weight-of-Evidence Interpretation (CLH Report Section 10.10, pages 21-104)

Many of the in vivo studies relied upon in the CLH report provide insufficient reporting of key indicators of systemic toxicity (e.g., food and water intake, body weight, and clinical indicators) and do not allow for confident determination that reported reproductive findings are independent of, and not secondary to, general toxicity. This is an essential distinction because the CLP criteria for Repr. 1B “…requires clear evidence of an adverse effect on sexual function and fertility in the absence of other toxic effects, or, if co-occurring, demonstration that the reproductive effect is not a secondary, non-specific consequence of general toxicity”. At the same time, the analysis and conclusions in Section 10.10 rely heavily on studies that do not employ the integrated fertility endpoints central to reproductive toxicity classification under CLP (e.g., mating performance, conception, implantation efficiency, litter size, offspring viability), instead emphasizing intermediate or surrogate endpoints (e.g., hormone concentrations, steroidogenic enzyme activity, histology, sperm counts/motility) that, while potentially informative for hazard identification, do not on their own demonstrate impaired reproductive performance as defined under CLP Annex I (ECHA, 2017), a concern that is particularly material given the proposed classification as Repr. 1B.

The CLH report states that only studies with Klimisch Scores 1 and 2 were included. While Klimisch scoring indicates a level of methodological reliability, it does not assess the regulatory relevance of endpoints for fertility classification, nor does it distinguish surrogate biological measures from functional fertility outcomes, nor does it assess whether study designs can demonstrate impaired reproductive performance. Given the regulatory implications of a Repr. 1B proposal, IADR urges further analysis to assess endpoint relevance and study design capability to detect functional fertility impairment.

Surrogate Endpoints and General Toxicity Confounding (Section 10.10.1.1, p. 22-94)

Table 15 is presented as a coherent weight of evidence, with claims that “all except one” study shows male fertility toxicity at doses of 0.104–21.6 mg/kg bw/day and “in absence of marked or less marked general toxicity.” However, the animal studies summarized largely comprise high-dose drinking-water or gavage designs focused on surrogate endpoints (e.g., steroidogenic enzymes, endocrine markers, histological findings) without measuring integrated fertility outcomes. Moreover, multiple studies originate from the same laboratory groups using similar experimental approaches and outcome measures; hence, the apparent internal consistency may reflect repeated use of similar designs rather than independent replication across diverse methods and blinded outcome assessment. Therefore, they do not meet the evidentiary requirements for reproductive toxicity classification under CLP Annex I. Selected examples illustrate why several studies reported to show male fertility toxicity do not in fact demonstrate functional fertility impairment:

- Das et al. (2006) primarily assessed steroidogenic enzyme activity (e.g., Δ⁵,3β-HSD, 17β-HSD), plasma hormones (testosterone, FSH, LH), and germ cell quantification at a spermatogenic stage. These endpoints are considered biological surrogates that may indicate fertility potential, but they are indirect measures and do not constitute direct evidence of reduced fertility performance as defined under CLP Annex I.

- Ghosh et al. (2002) that is derived from the same laboratory group, included sperm count, however it did not assess functional sperm parameters or measure reproductive outcomes, limiting interpretability for fertility impairment under CLP Annex I.

- Gupta et al. (2007) reports adverse changes in male reproductive parameters at relatively low estimated doses, however, does not, on its own, demonstrate impaired fertility as defined in CLP Annex I. Further, endpoints such as sperm motility and density are susceptible to observer-dependent measurement bias when assessed without automated systems, blinding, and inter-observer reproducibility reporting. Where these safeguards are not documented, confidence in effect magnitude and study weight should be reduced accordingly.

Additionally, high-dose drinking-water studies reporting mortality or overt systemic toxicity at higher concentrations (e.g., Elbetieha et al., 2000) challenge the report’s general statement that reproductive effects occur in the absence of general toxicity, while reports of reversibility (e.g., Chaithra et al., 2020b) and pubertal-only exposure without adult fertility evaluation (e.g., Wang et al., 2024) further complicate inference regarding sustained functional fertility impairment.

Table 16 reinforces this concern: most studies (n≈33) focus on sperm parameters or spermatogenic markers rather than downstream fertility outcomes, with limited pregnancy/litter measures and substantial heterogeneity in study design and results, including null findings and evidence of reversibility. Accordingly, the narrative conclusion conflates sperm parameter changes with male fertility impairment and overstates certainty without clearly separating intermediate endpoints from functional reproductive outcomes.

Table 17 summarizes 15 rodent studies evaluating female sexual function and fertility, reporting changes in ovarian/uterine weight, histological alterations, and hormone concentrations, with fewer studies addressing pregnancy- or embryo-related outcomes. However, most endpoints are structural, histological, or endocrine proxies rather than comprehensive fertility outcomes (e.g., mating success, implantation efficiency, litter size or offspring survival). Additionally, several studies report reproductive findings in parallel with reduced food intake and/or body-weight loss, which can independently disrupt ovarian function, estrous cyclicity, and reproductive organ weights. Key uncertainties therefore include predominance of surrogate reproductive endpoints, limited assessment (or inadequate control) of systemic toxicity, small group sizes, single dose designs, and potential confounding due to nutritional status and weight change. Consequently, while the dataset indicates potential adverse effects on female reproductive tissues at high exposures, the evidence for direct impairment of female fertility remains heterogeneous and subject to uncertainty.

Table 18 reports decreases in ovary and uterus weight in several animal studies following sodium fluoride exposure at doses generally ≥10 mg/kg bw/day, which are approximately 15–30 times higher than the EFSA tolerable upper intake level for fluoride in adults (0.12 mg/kg bw/day, equivalent to 7 mg/day), and substantially higher than typical population intakes. As these effects frequently occur alongside reductions or gain in body weight and given the sensitivity of reproductive organ weights to estrous cycle stage and systemic nutritional status (which was not controlled for), the relevance of these findings to human exposure scenarios and to direct female reproductive toxicity remains uncertain.

Overall interpretation and implications for classification

Taken together, IADR recommends that the evidence in Section 10.10 on reproductive toxicity be interpreted with extreme caution and that the evidence does not support a new classification. While a number of animal studies report histological alterations of the ovary and uterus, changes in reproductive hormone levels and effects on estrous cyclicity or selected fertility parameters following sodium fluoride exposure, these findings are predominantly observed at relatively high dose levels and frequently occur in parallel with reduced food intake and/or body-weight loss. In addition, estrous cycle stage was not controlled for in studies assessing hormone concentrations or uterus endpoints, limiting interpretation of these effects. Only a limited number of studies assessed integrated fertility outcomes, and where available, showed heterogeneous results including multigeneration studies showing minimal or no effects on key fertility indices. Furthermore, the exposure levels used in many experimental studies substantially exceed typical human intakes, including the tolerable upper intake level for fluoride, and the available human data are mixed and subject to confounding. Overall, these important considerations introduce uncertainty regarding the specificity and human relevance of the reported effects in this section.

Given the report’s proposed classification as Repr. 1B, IADR encourages the RAC to more explicitly: (i) separate surrogate mechanistic/intermediate endpoints from functional fertility outcomes; (ii) address susceptibility to bias (including observer-dependent measures without blinding/reproducibility documentation); (iii) evaluate the role of systemic toxicity and nutritional confounding; and (iv) clarify how the available studies satisfy CLP Annex I expectations for demonstrating impaired reproductive performance.

Thyroid effects and endocrine disruption: Category 1 evidence threshold not met on current record (CLH Report Section 11, pages 106-182)

The CLH report’s endocrine rationale relies materially on thyroid endpoints and an asserted linkage to neurodevelopmental outcomes. It is important to note that scientific literature confirms that thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurements are insufficient and an inappropriate endpoint for fully assessing developmental neurotoxicity (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1998; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2025). The report itself acknowledges variability and limitations in the thyroid evidence base, for example, it notes that some goiter studies were not considered relevant due to quality limitations, and that available data did not confirm a clear association with T3/T4, with thyroid disease risk evidence considered too limited for dose-response analysis (Section 11.1.2.1.1). IADR would therefore like to emphasize the methodological concerns that directly undermine the reliability of pooled estimates and dose-response modelling used to support endocrine conclusions:

- Extreme heterogeneity in thyroid meta-analyses (Section 11.1.2.1.1, p. 114 - 115): The CLH report ignores the high heterogeneity, leading to inconsistencies in the reported effect sizes (Iamandii et al, 2024). The unexplained heterogeneity (TSH – 1. water F I2 = 100%; 2. Urinary F I2 =100%; 3- Serum I2 =99%) shows no single common effect and dose-response modelling is not meaningful in that context. The reported thyroid hormone effects are variable in direction and magnitude, and important confounders such as iodine status are frequently unmeasured or inadequately controlled. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn from meta-analyses when such high unexplained heterogeneity is observed (US NTP, 2019b; Crippa et al. 2016).

- Selective interpretation of key studies (Section 11.1.2.1.1 - Table 20): the CLH report emphasises significant findings in some analyses while ignoring null findings for urinary fluoride and intake metrics, although it acknowledges limitations such as possible reporting bias. For example, the report cites the adverse effect found in six analyses but ignores the lack of effect with urinary fluoride and fluoride intake. Additionally, the report concludes that there is sufficient evidence that fluoride exposure, including developmental exposure, can affect the thyroid. However, it ignores ECHA CLP guidance criteria (ECHA, 2024) that “increased thyroid weight and thyroid follicular cell hypertrophy/hyperplasia are commonly observed in rodent toxicity studies. These effects are T-mediated and can therefore be considered as an indication of reduced serum THs”. In addition, the CLP guidance mentioned that a “proper tissue concentration of THs is crucial for proper tissue function, during all phases of life, but the consequences of improper tissue concentration differ depending on the life-stage exposed. It should be noted that even small changes in foetal thyroid hormone levels (e.g. due to decrease of maternal TH levels) may have an influence on adverse outcomes, particularly those related to developmental neurotoxicity”.

- Limited direct thyroid endocrine activity evidence (Section 11.1.4, p. 161 - 164): the CLH report’s own evidence tables indicate that sodium fluoride has substantial gaps in evidence for direct, thyroid-relevant endocrine activity. Specifically, the report notes that the ToxCast analysis indicated that sodium fluoride was tested in 56 assays (19/01/2023) studying only neurodevelopment and cell cycle endpoints, and that “NaF was inactive in all these assays” with “no available data in key thyroid-relevant assays” for thyroid hormone receptors (THR), sodium/iodide symporter inhibition (NIS), or thyroid peroxidase (TPO). In addition, the literature review underpinning the endocrine activity tables identified only four in vitro/ex vivo thyroid-related articles (Table 26). The report further acknowledges that many in vitro studies used sodium fluoride primarily as a cytotoxic agent or as a prototypical inducer of cAMP signaling, rather than to test endpoints directly relevant to thyroid hormone synthesis or secretion, and that exposures were often at very high concentrations, sometimes exceeding cytotoxic thresholds, limitations that reduce interpretability for endocrine hazard identification. These evidence-table limitations suggest that the endocrine activity evidence for the thyroid axis is limited in scope and largely indirect.

Further, the CLH report itself states that fertility effects in males are not predominantly driven by endocrine mechanisms. Additionally, and importantly, the report does not include studies where TSH changes are demonstrated at typical drinking water concentrations. Furthermore, although the report invokes established thyroid-related AOPs to support biological plausibility, while these AOPs are valid, in general sustained and specific perturbation of key endocrine events by sodium fluoride at relevant exposure levels has not been demonstrated. This internal inconsistency demonstrates that the dossier as submitted does not support that the CLH endocrine disruptor Category 1 threshold has been met, particularly given that Category 1 requires endocrine activity, adversity, and a biologically plausible link.

Failure to include study limitations (CLH Report Section 11.1.2.2.1)

- On page 139, the CLH report includes a statement that outlines the strengths of the included studies; however, major limitations are omitted (Guichon et al. 2024b). (i). The Maternal–Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) study did not control for IQ testers - six different IQ testers were employed, each assigned to a different city. Hence, it is impossible to separate the effect of fluoride from the impact of the CITY and IQ testers. Site-specific IQ data included in the master’s thesis (Green 2018) that formed the basis of Green et al. (2019) indicated very large differences in mean IQ among those 6 Canadian cities, suggesting poor inter-examiner reliability. (ii). The Early Life Exposures in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants (ELEMENT) study has several other limitations that are not discussed, including failure to meet standards for acceptable quality as outlined by the US Environmental Protection Agency (Kumar et al. 2025). (iii). The Goodman et al. (2022) study did not address the confounding impact of salt, and it raises concerns about the validity of spot maternal urinary fluoride as a long-term measure of fetal fluoride exposure, given the lack of agreement between urinary and plasma fluoride biomarkers (Thomas et al 2016).

- On page 139, the CLH report also states that “…all the studies, except one (Ibarluzea et al. 2022), showed an association between developmental fluoride exposure and the impairment of the cognitive function in children.” However, there is a failure to note that there are only four maternal urinary fluoride studies. It did not include Singh et al (2025) from Bangladesh because the authors constructed a cohort study from a randomized clinical trial. Neither Ibarluzea et al. nor the Grandjean et al. studies showed an association between fluoride and impaired cognitive function.

- On page 139 the CLH report further states that “The association between prenatal fluoride exposure and IQ was significant. The studies also indicated that the effects on IQ of prenatal fluoride exposure were different among sex. Boys were more sensitive to the fluoride exposure than girls in most of the studies (Green et al. 2019, Goodman et al. 2022a, Farmus et al. 2021, Cantoral et al. 2021).” However, the MIREC and ELEMENT studies show internal inconsistency and lack external validity. Both are based on convenience sampling. The differential effect by sex reported in the Green et al. (2019) paper is contradicted by Till et al. (2020) and Farmus et al. (2022) which did not observe these effects in any of the other cohort studies.

Key additional evidence the CLH report should address transparently

While some studies may not have been actively excluded, the evidence base as presented within the report is not current, and omits several consequential datasets that materially affect the weight of evidence and resulting classification, and therefore should be addressed transparently, including:

- Bennekou SH, Allende A, Bearth A, et al. (2025). Updated consumer risk assessment of fluoride in food and drinking water including the contribution from other sources of oral exposure. EFSA Journal. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2025.9478.

- Duan Q, Jiao J, Chen X, Wang X. (2018). Association between water fluoride and the level of children’s intelligence: a dose–response meta-analysis. Public Health. 154:87-97.

- Gopu BP, Azevedo LB, Duckworth RM, Subramanian MKP, John S, Zohoori FV. (2022). The Relationship between Fluoride Exposure and Cognitive Outcomes from Gestation to Adulthood—A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20(1):22.

- Guth S, Hüser S, Roth A, et al. (2020). Toxicity of fluoride: critical evaluation of evidence for human developmental neurotoxicity in epidemiological studies, animal experiments and in vitro analyses. Arch Toxicol. 94(5):1375-1415.

- Guth S, Hüser S, Roth A, et al. (2021). Contribution to the ongoing discussion on fluoride toxicity. Arch Toxicol. 95(7):2571-2587.

- Health Canada. Expert Panel Meeting on the Health Effects of Fluoride in Drinking Water: Summary Report. 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/water-quality/expert-panel-meeting-effects-fluoride-drinking-summary.html.

- Kumar J V., Moss ME, Liu H, Fisher-Owens S. (2023). Association between low fluoride exposure and children’s intelligence: a meta-analysis relevant to community water fluoridation. Public Health. 219:73-84.

- Ministry of Health. New Zealand Government. Community Water Fluoridation: An Evidence Review. https://www.health.govt.nz/publications/community-water-fluoridation-an-evidence-review

- Miranda GHN, Alvarenga MOP, Ferreira MKM, et al. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between fluoride exposure and neurological disorders. Sci Rep. 11(1):22659.

- Taher MK, Momoli F, Go J, et al. (2024). Systematic review of epidemiological and toxicological evidence on health effects of fluoride in drinking water. Crit Rev Toxicol. 54(1):2-34.

- The Academy of Medical Sciences. (2025). Evidence synthesis report on the optimal concentration of water fluoridation in the UK. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/academy-water-fluoridation-report-2025. Veneri F, Vinceti M, Generali L, et al. (2023). Fluoride exposure and cognitive neurodevelopment: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ Res. 221:115239.

IADR strongly supports incorporating these reviews into an updated evidence synthesis with transparent, domain-based risk-of-bias framework especially to the observational human studies (e.g., exposure assessment, confounding, selective reporting), and explicit handling of inconsistency.

In summary, the evidence presented in the CLH report does not meet a reasonable scientific threshold to justify reclassification or labelling of sodium fluoride as proposed. The report’s central inferences, particularly regarding developmental neurotoxicity and thyroid-mediated endocrine disruption, are weakened by substantial limitations in exposure characterization (including reliance on indirect proxies), residual and unquantified confounding, unexplained heterogeneity across studies, inconsistent findings in exposure ranges most relevant to population use, and an insufficiently coherent mechanistic narrative linking TSH to neurodevelopmental adversity. Due to the notable uncertainty within this report, overstating certainty in the hazard conclusion can produce regulatory outcomes that are not proportionate to, or supported by, the underlying evidence-based science

Reclassifying sodium fluoride on the basis of the presented studies risks unintended consequences that would be harmful to human health. Hazard classifications can materially influence availability, access, and uptake of fluoride-based preventive interventions that are foundational to caries prevention at the population level, particularly for children and for underserved communities with higher disease burden and fewer alternatives. Accordingly, the IADR urges the CLH submitter to reassess the weight-of-evidence with a transparent appraisal of study quality and relevance, and to fully consider higher-quality systematic reviews and authoritative evidence assessments identified in this stakeholder comment. If uncertainty persists, the RAC should ensure that any final opinion reflects that uncertainty explicitly and adopts a proportionate classification that is scientifically defensible.

IADR welcomes and encourages additional high-quality research, especially prospective studies with stronger exposure assessment, rigorous control of key confounders (including nutrition and co-exposures), and mechanistic research that can clarify biological plausibility and dose relevance, so that future evaluations can be based on more robust and internally consistent evidence. IADR stands ready to work with the ECHA to further define and clarify the impact of fluoride on human health.

The IADR thanks the European Chemicals Agency for the opportunity to provide these comments. If you have any further questions, please contact Dr. Makyba Charles-Ayinde, Director of Science Policy, at mcayinde@iadr.org.

Sincerely,

Christopher H. Fox, DMD, DMSc Pamela C. Yelick, Ph.D.

Chief Executive Officer President